The Hall has enshrined more than 400 athletes and coaches as it celebrates its 60th anniversary, but the organization recognized its first volleyball athlete Danielle Scott and first rodeo cowboy T. Berry Porter on Saturday.

As for seconds, legendary quarterback Peyton Manning became the second Manning (Archie Manning) inducted and the third father-son duo. The Mannings join Dub Jones (Tulane All-American and NFL All-Pro) and Bert Jones (LSU All-American and NFL MVP) as well as sprinters Slats Hardin (NCAA champion and Olympian) and Billy Hardin (NCAA champion and Olympian).

The seventh comes into play with Max Fugler, who is the seventh member of the 1958 LSU football national championship to be inducted.

And then there’s Les Miles.

There isn’t just one word (or number) that could sum up the quirky former LSU coach that is taking the reins at Kansas. There was family, clapping, gutsy decision-making and Tennessee taunting.

Miles, who was “forced” to lead a clapping tutorial in which one’s “hands don’t sustain injury,” pointed at former Tennessee coach Phil Fulmer and jokingly said he’s “coming after Fulmer” in reference to Tennessee’s Monday night win in Tiger Stadium after Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005.

The famous grass-eating Miles had the last laugh in 2007 when LSU topped Fulmer’s Vols in the Southeastern Conference Championship en route to the national championship.

But family was Miles’ cornerstone.

“When (then-LSU athletics director) Skip Bertman interviewed me, he asked me ‘Family or football,’ and I said both,” Miles said. “I will fight like hell to do both.

“You’ll get a great football coach, but I’m going to be a great father and husband. Skip told me this what you’re going to do, this is what you’ll get paid and this is how much success you’ll have – and he was right about all of it.”

The Tennessee teasing continued with Manning as host Lyn Rollins asked Manning about the number of times he cried during the documentary “The Book of Manning,” which detailed the Manning boys’ life.

“It was a good documentary on my dad and how he was a wonderful father,” Peyton said. “I think they showed a few too many crying videos.

“You think at what point do you stop filming your three-year old son getting kicked in the head by his older brother? Maybe you should go and help the kid. They never mentioned that here’s 3-year-old Peyton playing against a bunch of 8-year-olds.”

Manning never had the strongest arm or fleetest of feet – former Newman High coach Tony Reginelli told him Saturday that he “couldn’t run out of sight in a week.”

It was Manning’s preparation that led him to be the first NFL quarterback to win Super Bowls with two different teams (Indianapolis and Denver).

But of all the memories Manning has created, he said throwing passes to his brother Cooper as a high school sophomore topped the list.

“We would play on the Superdome turf while Dad was doing interviews as kids, and that season in high school was the best,” Manning said. “I had 120 completions that year, and 90 were to Cooper because he was the best player.

“He had a neck injury and had to stop playing. But watching how he handled that injury helped me face my injuries and adversity in my career.”

Former Louisiana Tech quarterback Matt Dunigan played the position with his own spunk.

Dunigan, decked out in a blue tuxedo, didn’t hesitate when asked why he chose Louisiana Tech with interest from Texas among others.

“(Louisiana Tech assistant coach E.J. Lewis) came for a home visit, and he didn’t spit for the entire six hours when he chewed tobacco,” Dunigan said. “That was an easy sell.”

Dunigan, who broke multiple Terry Bradshaw records at Louisiana Tech, is a CFL Hall of Famer who won two Grey Cups. Dunigan had the Grey Cup in tow for his Louisiana induction.

“I knew I was vertically challenged, but God gave me a weapon in this right arm,” Dunigan said. “I fit pretty good in the CFL.

“I credit my family moving down to Texas from Ohio – the Dallas competition was sink or swim. I fought to get on a football field every day, and sometimes I got in two or three fights a day. Well we would get detentions but couldn’t serve them because of football practice. I had to burn off those detentions, and I would come to practice with my ass bleeding (from spankings).”

Another player who could dish out punishment was LSU’s Fugler.

Fugler played more minutes of the 1958 championship team than any other Tiger, taking pride in his work on the offensive and defensive lines as well as at linebacker.

One of the best “winners” as he was a part of a 54-game winning streak at Ferriday High, Fugler talked about losing and how that boosted his career.

“You can’t win every time, and the losses hurt me bad,” Fugler said. “You have to learn how to be a good loser or you’ll never be a good winner.

“Success is ahead of work only in the dictionary.”

Peabody Magnet boys basketball coach Charles Smith (1,039 wins) is just 32 victories away from becoming Louisiana’s all-time winningest high school basketball coach.

Green Warhorse pom-poms flailed in the air when his name was called, and Smith fought back tears when he spoke of his “church-house school teacher mother and World War II veteran father.”

“By all laws, I shouldn’t be here tonight because by today’s standard, I was an at-risk kid,” said Smith, who teaches trigonometry and calculus. “My mother taught me every day of my life, and my father taught me how the man of the house goes to work to support a family.

“Kids don’t care what you know until they know that you care, and I walked into the classroom every day and I was there for their success.”

Southern baseball coach Roger Cador had a similar level of winning, but the Ventress native spoke about how he didn’t have any formal education until his teenage years.

“I was born into a sharecropping family, and I didn’t have the ability to read or write growing up,” Cador said. “When I did go to school, I was teased mercilessly.”

What Cador did have was a golden voice and smile that drew future MLB Hall of Famer Rickie Weeks to Southern.

Cador won more than 900 games as Southern became the first historically black program to win an NCAA Regional game when they topped No. 2 Cal-State Fullerton in 1987.

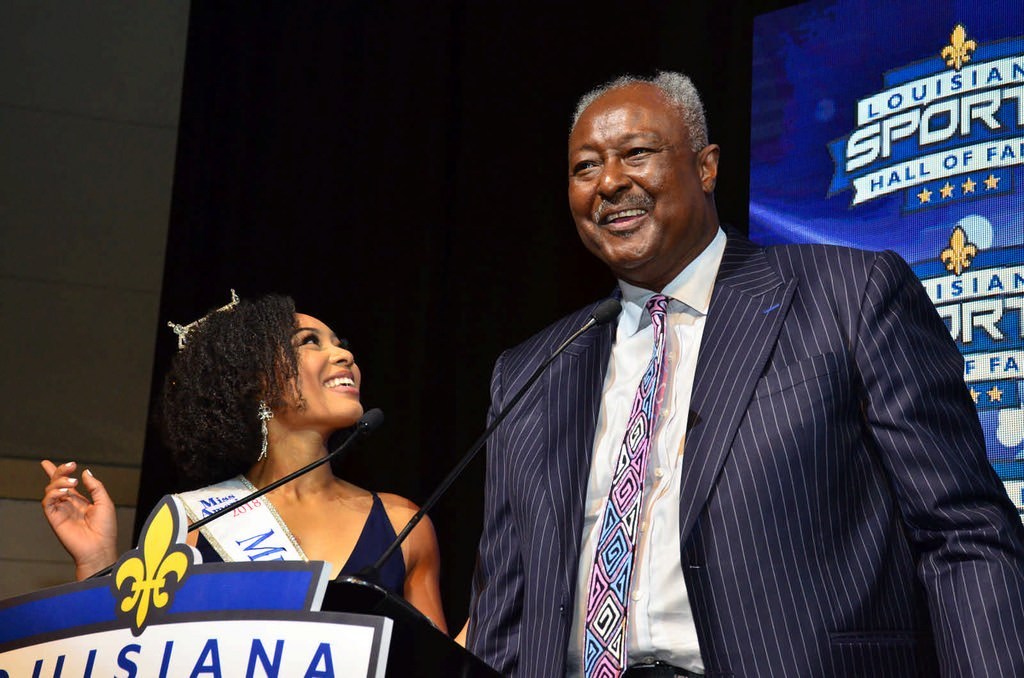

It turns out the coach can’t sing well as he led the crowd in “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” with Miss Louisiana Holli’ Conway.

Louisiana Tech radio broadcaster Dave Nitz had much more pleasing vocals as he’s called historical moments as 44 seasons as the voice of the Bulldogs and 58 overall.

Nitz, who was one of two recipients of the Distinguished Service Award, has called more than 7,000 games between Louisiana Tech and minor league baseball, the game that was his first love.

But it’s a career that almost never started in the West Virginia hills.

“After I finally got a job in Spencer, West Virginia, and started the Big Dave Night Beat, the station decided they wanted to get more involved in the community with high school football,” Nitz said. “The manager asked if anybody had any experience, and I said that I played some high school sports.

“The manager looked around and said, ‘Are you sure nobody else wants to do this?”

Nitz earned the nickname “Freeway Dave” because he exceeded his mileage on an “unlimited rental car.”

While Nitz could be found burning up roads across the country, T. Berry Porter could always be found on a horse or a tractor.

When Porter received the call that he was going to be a Hall of Famer, the Vernon Parish native was on his tractor.

After becoming a member of the Rodeo Hall of Fame in 2015, Porter is the first cowboy to be a Louisiana Sports Hall of Famer.

“I started roping around age eight, and I drove a car and had a homemade trailer,” said Porter, who won the world championship in calf-roping in 1949. “Back then, calves were 275 or 300 pounds, and I was just 150 pounds.

“I really enjoyed my time in that, and I made a lot of friends. I never thought I’d be here.”

Porter, 92, is the oldest inductee in the Hall.

Volleyball stud Danielle Scott certainly isn’t the oldest, but she had one of the longest professional careers. The five-time Olympian nearly qualified for a sixth games and helped the U.S. to two silver medals.

Called “Super Woman” by a former Long Beach State teammate, Scott is known for her “belligerent optimism.”

“My mom built a strong Christian foundation as a woman of God and integrity,” said Scott, who was injured in a domestic violence attack that killed her sister Stefanie. “Knowing who I am in Christ and knowing what the word says and His promises for me helped me in my career and to deal with circumstances that seem unfathomable.

“I lost my sister in an attack that landed me in the hospital. When I was unable to pray for myself, there were so many who were praying for me, and I had an overwhelming sense of comfort and peace.”

Marie Gagnard, the Dave Dixon Sports Leadership Award winner, found her place when her mom made a random call to the Alexandria Town Talk because her daughters were bored over the summer.

Gagnard has made her mark as a tennis official and will call her 30th U.S. Open, including 26 straight, this year.

But it’s Gagnard’s start in officiating that raises eyebrows.

“I was in my first year of teaching, and I get a call from Robert Kavanaugh that they need officials for this exhibition in Baton Rouge between Bjorn Berg and Jimmy Connors, who were the top two players that year,” said Gagnard, who overcame two bouts of thyroid cancer which affected her voice. “I got a 15-minute crash course in officiating, and I was thrown out here.

“I walked off the court and thought it was a lot of fun. I didn’t know if I was any good, but I had fun.”

A record 822 folks attended Saturday night’s ceremony, and plenty said the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame might not have been anywhere near the size and grandeur without journalist Phillip Timothy.

Timothy suffered a horrific vehicle accident which required eight surgeries, and from his hospital bed, helped lay the foundation for the Hall to move from a couple of glass cases in Northwestern State’s Prather Coliseum to a building that won worldwide architectural awards on Natchitoches’ Front Street

“I couldn’t bear any weight for awhile, and I had to have something to do,” said Timothy, a veteran journalist used to burning midnight oil. “We talked about needing a permanent museum for a state that is so blessed with athletes.

“We got sponsors and other people believing in us, and now we have a wonderful place for our sports heroes.”

-30-