By JOHN JAMES MARSHALL/Designated Writers

If you are baseball fan, you are kind of obligated to know the significance of April 8. It’s one of those I-know-where-I-was dates in your sports memory bank.

And when April 8 rolls around every year, a simple mental acknowledgment will suffice. No need to take a day off from work.

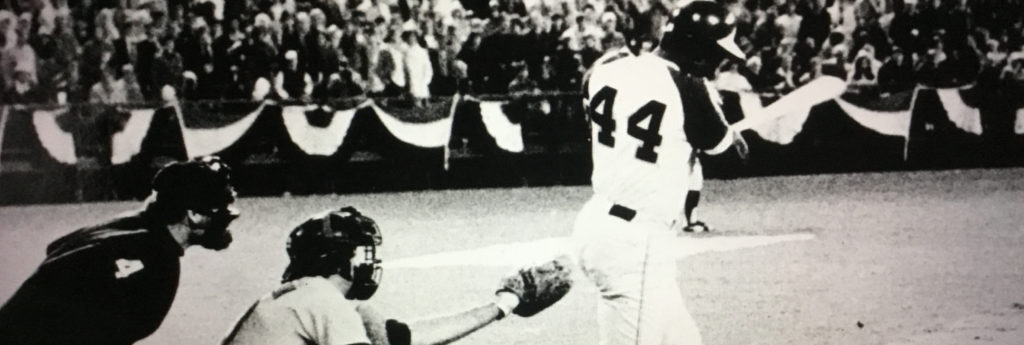

It was on April 8, 1974, that Hank Aaron — The Hammer — hit the home run that broke Babe Ruth’s record which, at the time, was the most revered record in all of sports (and it wasn’t even close).

There are so many major and minor subplots to that night at Atlanta Stadium (see, there’s one! It wasn’t re-named Atlanta-Fulton Country Stadium until the next year). There is baseball significance, racial significance, cultural significance, and Shakespearean significance. Wait … how’s that again, you say?

Yes, the night Hank Aaron belted an Al Downing pitch in the fourth inning over the left field fence, I was just where you’d expect me to be. Backstage in the Jesuit High School gym getting ready to deliver one of my four lines as Angus in the Shakespearean play “Macbeth.”

“He did it,” somebody whispered to me and let me assure you he wasn’t referencing McDuff’s guilt in the whole beheading situation. (Who couldn’t have seen that coming a mile away?)

No, I knew exactly what that meant and I had to take a moment to let it sink in that I had missed one of the great moments in sports history in order to walk on stage and tell some dude in bad clothing that he had ascended to the Thane of Cawdor.

“We are sent

To give thee from our royal master thanks;

For The Hammer has ripped a 1-0 fastball,

and gone yard.”

It is hard to imagine that any sports record will ever match the buildup of Aaron’s homer. Funny thing is, there was a time when baseball fans thought it was Willie Mays who was going to break the record. After the 1966 season, Mays was in second place with 542 homers. He was 35 years old at the time but he had just hit 37 homers that season. You figure if he comes close to that for the next few years, it’s going to get interesting.

At that same time, Aaron was in 10th place with 442.

But Willie rapidly began to decline — his next five season home run totals were 22, 23, 13, 28, 18 — and by the end of the 1971 season, Aaron was now in third place (he hit 47 that year). He was only seven behind Mays — and was three years younger.

Game on.

Aaron hit 34 when he was 38 years old and 40 when he was 39 to finish the 1973 season one behind Ruth. (Another side note — Aaron hit #712 in Houston and had a week-long home stand to end the 1973 season. But it wasn’t like Atlanta was whipped into a frenzy; there were crowds of 10,211 and 5,711 for two midweek games. Aaron did uncork No. 713 on a Saturday and 40,000 showed up for the final game on a Sunday, but all he did was get three singles to raise his average to .301.)

So there was only one story line when the 1974 season started but the Braves started on the road in Cincinnati. (Nice job, schedule makers; way to have a great sense of history.) Everybody knew he wanted to break the record at home and the Braves said they were going to hold Aaron out of the opening series. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn put the kibosh on that and ordered that he play in two of the three games against the Reds.

The Hammer went deep on his first swing on Opening Day to tie Ruth and then sat out the next day (“load management?”), meaning that he had to play in the third game before heading home to Atlanta. Here’s why I love Hank Aaron — on that day when he was forced to play, he struck out twice and had a groundout. Even as a 40 year old, do you know how many other times he struck out twice in a game that entire season? Two. Take that, Commissioner!

And on the next night, history was made in front of 53,775 people, none of whom were named Bowie Kuhn.

The racial taunts that Aaron endured are well known and he has always been a gracious and likable legend in baseball history. The U.S. Post Office estimated that he received 930,000 pieces of mail that year and Aaron admits most of it was kind. But hundreds of the letters were not.

When he broke the record, he was admired, but he was not loved like Willie Mays was. But as time has passed, Aaron has become a beloved figure, not only in baseball but in all of sports. He is no longer “the home run record holder,* but he still leads in career RBI and total bases — and hasn’t played since 1976.

It’s taken decades, but Hank Aaron has gotten what he deserved.